Technology competition between nations: Views from industry leaders

Introduction and caveats

Technology competition has become a major fault line of geopolitics. The United States and its allies and partners have recently taken aggressive steps to manage that competition. Most notably, the U.S. and EU have each passed a “Chips Act” designed to bolster domestic semiconductor fabrication, while the U.S. has implemented an array of new export controls and administrative measures meant to curtail China’s domestic high-end semiconductor industry. For its part, Beijing has both doubled down on the strategy of technology self-reliance and undertaken restrictive measures of its own, such as the recent ban placed on using Micron products in telecommunications infrastructure. Entrepreneurs, firms, and research labs in both the U.S. and China are racing to seize the business and strategic opportunities exposed by the rapid adoption of OpenAI’s ChatGPT last fall.

Yet even as the U.S. and China grow more aggressive in their efforts to ‘win’ the global technology competition, how that competition plays out will not be decided solely by officials in Beijing and Washington, D.C. Businesses and technology firms scattered around the globe have a major role to play.

To gauge their perceptions of where technology is headed, we recently surveyed approximately 285 global executives, academics and researchers in the global technology industry for their views on how the industry will evolve. Roughly 100 respondents work for China-headquartered organizations, another 100 for US-headquartered organizations, and 50 for European-headquartered organizations. The remaining respondents were scattered across India, East Asia and Southeast Asia. Over 60% of all respondents worked in the semiconductor or high-tech hardware industries, with the remainder working for companies that are heavy users of semiconductor technologies, such as those in the software or automotive sectors. Although our sample was not randomly selected and is not fully representative, the survey data nonetheless serves as an important descriptive indicator of how industry leaders view the future of global technology competition.1

Several themes stand out. First, the U.S. is viewed as being in a stronger competitive position than is perhaps appreciated in Washington. Second, and conversely, China is perceived as facing significant headwinds, particularly in its push to develop leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing capabilities and in maintaining its global share of electronics manufacturing. Thirdly, despite the challenges faced by the U.S. and China, they are viewed to have a substantial lead over other regions, especially Europe, as locations to develop, commercialize and scale new technologies. Fourth, the future of the global technology industry is likely to be bifurcated and de-risked, with many firms continuing to serve both the U.S. and Chinese technology ecosystems — even as these two ecosystems grow more separate and distinct.

Substantial optimism about U.S. competitiveness

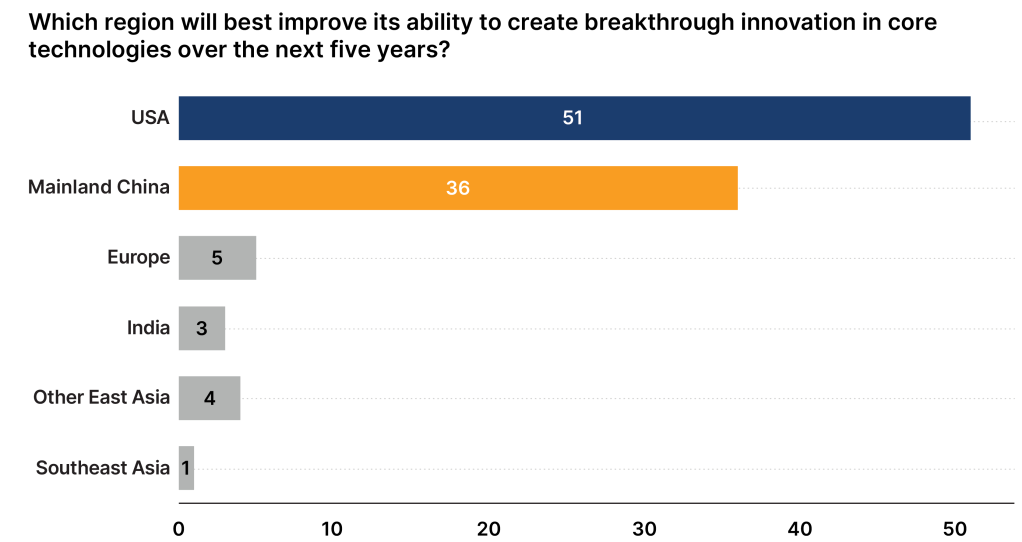

Although American officials often express concern that the U.S. has fallen behind in its capacity for innovation, their fears are not widely shared among the experts and executives surveyed. When asked about which regions or countries will best improve their competitiveness over the next decade, respondents are optimistic on both the United States and China in core technologies vis-à-vis the rest of the world. However, the U.S. was seen as far and away the country most likely to improve its ability to create breakthrough innovations in core technologies over the next five years.

Figure 1

Likewise, there is substantial optimism about the impact of U.S. government efforts to relocate leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing to the United States. Across all cohorts, survey respondents believe that the U.S. will gain the most share (among all other regions) in leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing.

Likewise, there is substantial optimism about the impact of U.S. government efforts to relocate leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing to the United States. Across all cohorts, survey respondents believe that the U.S. will gain the most share (among all other regions) in leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing.

Figure 2

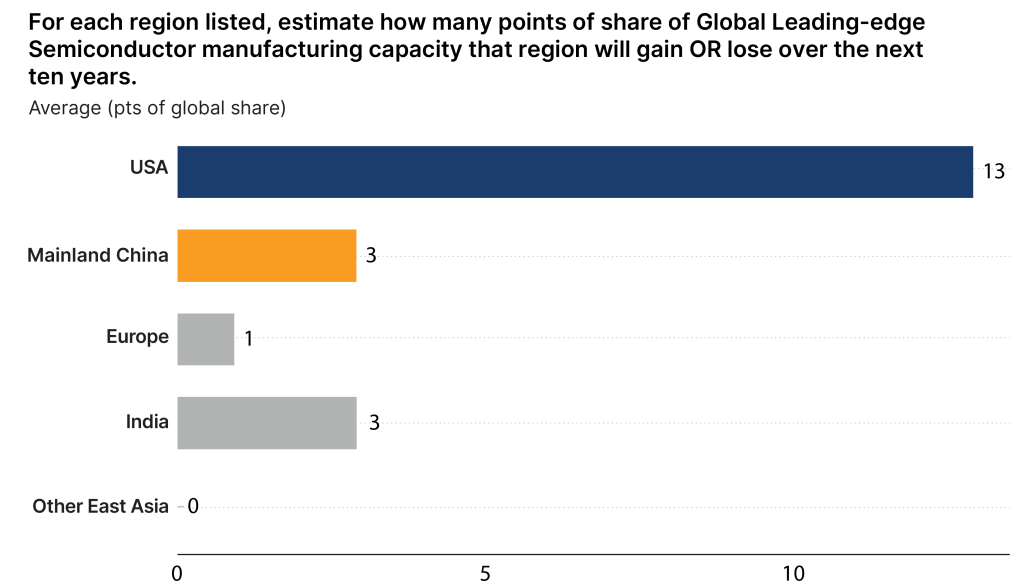

Further, the respondents also allayed concerns that U.S. policies are reducing America’s attractiveness for talent and capital. Although the survey included roughly equal numbers of participants from U.S. and China-headquartered firms, the respondents view the U.S. as 5 times more likely to outcompete China in attracting global capital and nearly 6 times more likely to attract the world’s best technical talent. This sentiment was universal — respondents from every country, region and industry segment perceive the United States as the most attractive global destination for talent and capital. Respondents at European, Indian and other Asian companies select the United States 6 times more often than China as the preferred location for talent, and 10 times more often as the preferred location for capital investment.

Figure 3

Given the role of talent in driving breakthrough innovation, the respondents also highlight talent as a key lever on which American officials should focus. When asked how the U.S. government could best help the semiconductor industry, more than half choose “allow more technical talent into the United States” as their first or second policy recommendation. By comparison, only one-third highlight “subsidies for fabs.”

Figure 4

If U.S. global competitiveness is a strategic priority for the US, the results suggest that the White House and Congress should focus far more on allowing entry to global technical talent.

China’s challenges in rising to global technology leadership

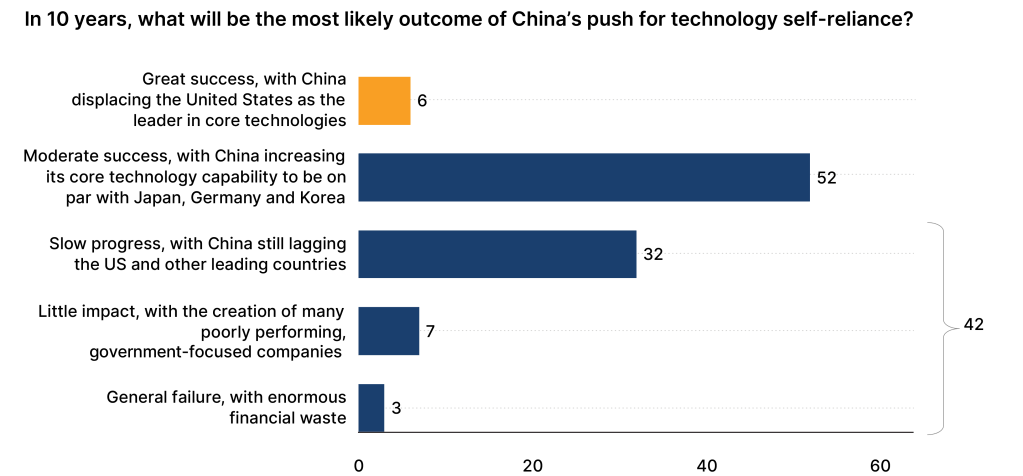

Despite pronouncements from U.S. policy makers and pundits that China is poised to outcompete the U.S. on innovation, experts do not believe China will ascend to the #1 position in the development of core technologies. Most notably, fewer than 10% of respondents believe China will surpass the technical capabilities of the United States over the next ten years, whereas more than 40% believe China’s technology self-reliance effort will have slow progress or even fail.

Figure 5

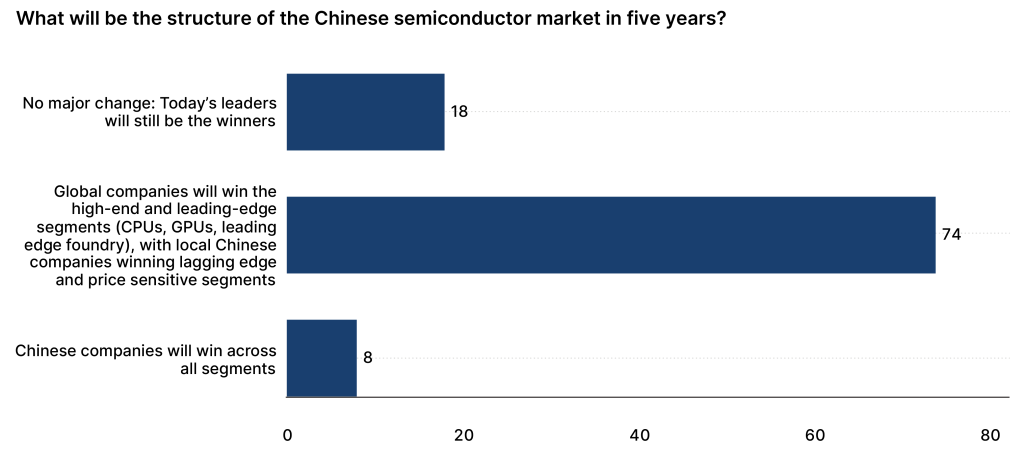

Respondents do not expect Chinese companies to be able to outcompete global companies for high-end and leading-edge chips even within China’s domestic market. For example, nearly 75% of respondents indicate that Chinese companies will only win in the lagging edge and most price sensitive sectors of the domestic Chinese market; over 90% of respondents indicate that the most advanced semiconductor segments in China, which are most critical for artificial intelligence leadership, are expected to be dominated by non-Chinese companies.

Figure 6

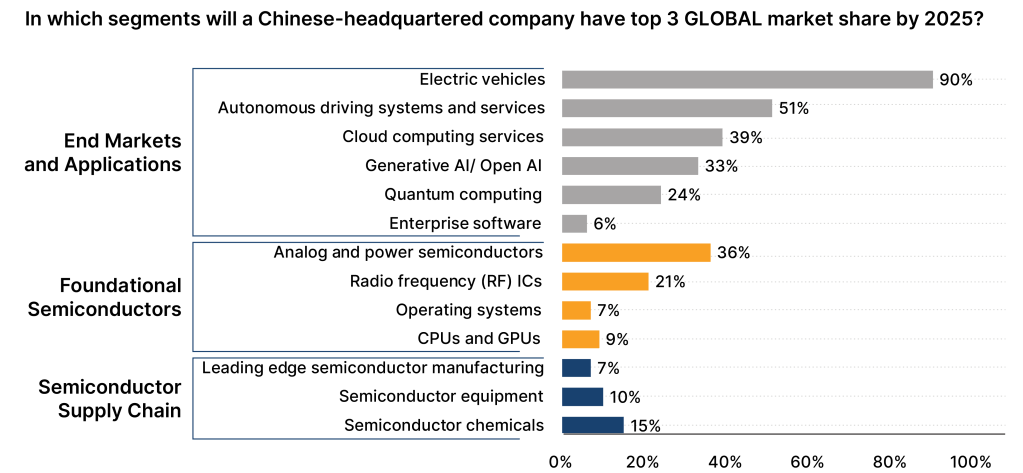

This disparity in expected performance of Chinese firms is seen below. Respondents are very optimistic that China will produce a top 3 global player in electronic vehicles, but only somewhat optimistic that Chinese companies will take global leadership in the cloud computing as well as the analog, power, and radio frequency semiconductor markets.

However, for the foundational technologies that underpin the datacenter, PC, smartphone and AI industries there is considerably less optimism, with less than 10% believing China can produce a top 3 global player in GPU, CPU or operating system industries. Respondents believe Chinese companies will faces similar challenges in the ‘upstream technologies’ that are used to build these high-end semiconductors, with only a small minority believing China will headquarter a top 3 global player in leading edge semiconductor manufacturing (7%), semiconductor equipment (11%) or semiconductor chemicals (15%). Finally, less than 10% indicate China could produce a global leader in enterprise software, which is the most profitable and fastest growing technology segment globally.

Figure 7

Notably, respondents working for American or Chinese companies share similar views regarding China’s competitiveness across the segments in Figure 7. For seven of the segments, Chinese respondents are slightly more optimistic than their non-Chinese counterparts, but for the other seven they are slightly more pessimistic.

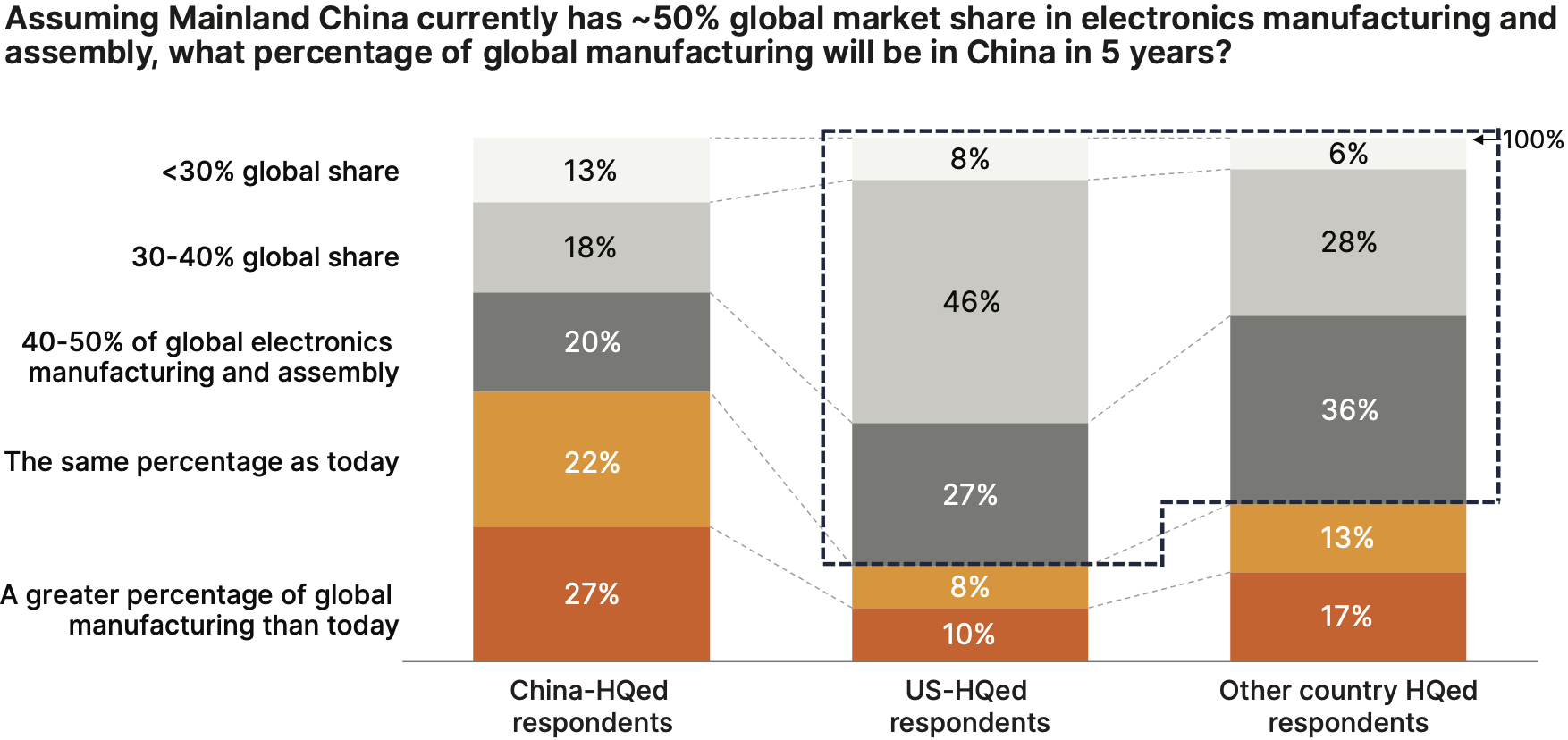

China’s challenges in gaining global share in advanced technologies could be mirrored by a loss in mainland China’s global share of downstream electronics manufacturing and assembly. More than half of all respondents, including 75% of respondents who work for non-Chinese companies, believe that Mainland China will host a smaller share of global electronics manufacturing capacity in 5 years than it does today.

Figure 8

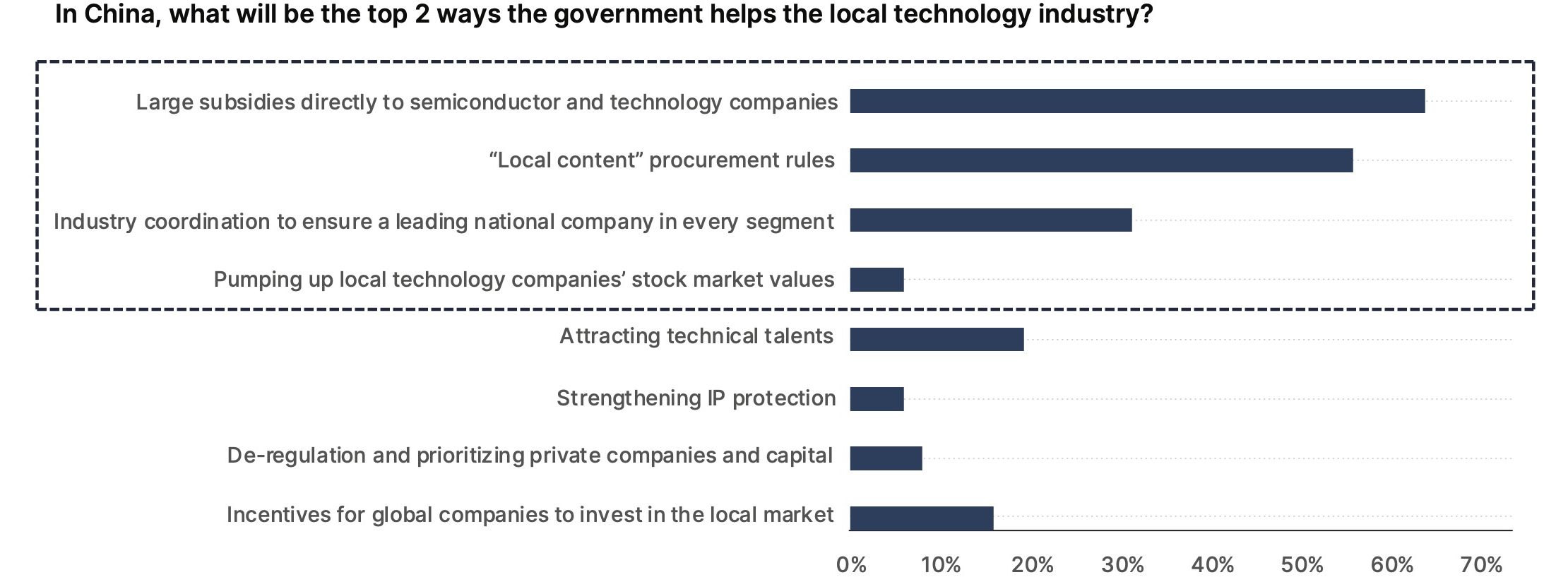

How is the Chinese government likely to respond? Respondents who operate in China expect government policies will focus on supporting local Chinese companies, primarily by providing large subsidies for local companies and imposing “buy local” procurement rules.

Figure 9

Little optimism for Europe as a ‘third pole’ of the global technology industry

In 2022, the European Union defined the “European Chips Act,” one of several EU programs designed to strengthen the EU technology industry and promote technology autonomy. Yet despite that announced investment and other announced European efforts, across every regional comparison question, respondents do not rate Europe highly. As the table summarizes below, respondents, by an order of magnitude, always indicate more optimism for the U.S. and China as global leaders versus Europe.

Comparison of responses for selected questions on regional competitiveness

| Question | Ratio of Selections (USA:China:Europe) |

| Most Improved Location for Creating Breakthrough Core Technology Innovation | 10:8:1 |

| Most Improved Location for Scaling and Manufacturing Core Technology Innovation | 8:9:1 |

| Incremental Points of Market Share in Leading Edge Semiconductor Manufacturing | 13:3:1 |

| Most Attractive Location for Top Technical Talent | 33:4:1 |

| Most Attractive Location for Global Capital Investment | 58:10:1 |

These results may owe at least partly to the demographics of the survey respondents, since more than two-thirds of them hail from American or Chinese-headquartered companies. However, it’s worth noting that the survey respondents from companies headquartered in Europe also collectively grade China and the U.S. higher than Europe across every regional comparison question above. (For example, less than 10% of European respondents believe that top global talent would select Europe as their preferred working location).

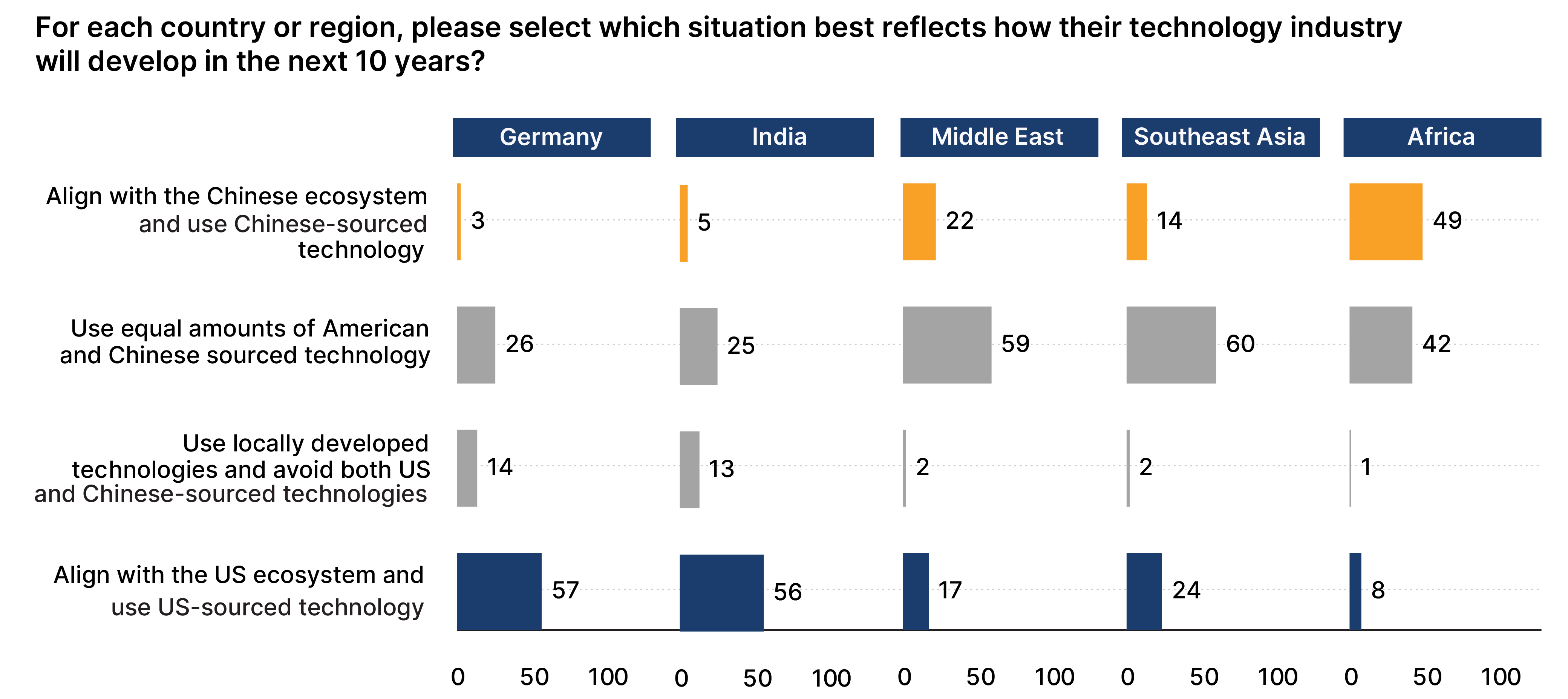

Beyond Europe, respondents also express clear differences by region with respect to how other countries approach technology development. Respondents expect Indian firms to align closely with the “US-led” ecosystem, whereas they anticipate companies in Africa will more heavily participate in the “China-led” ecosystem. In the Middle East and Southeast Asia, however, respondents expect loyalties will be more split, with companies equally likely to participate in American and Chinese technology ecosystems.

Figure 10

The future will be bifurcated—but not decoupled.

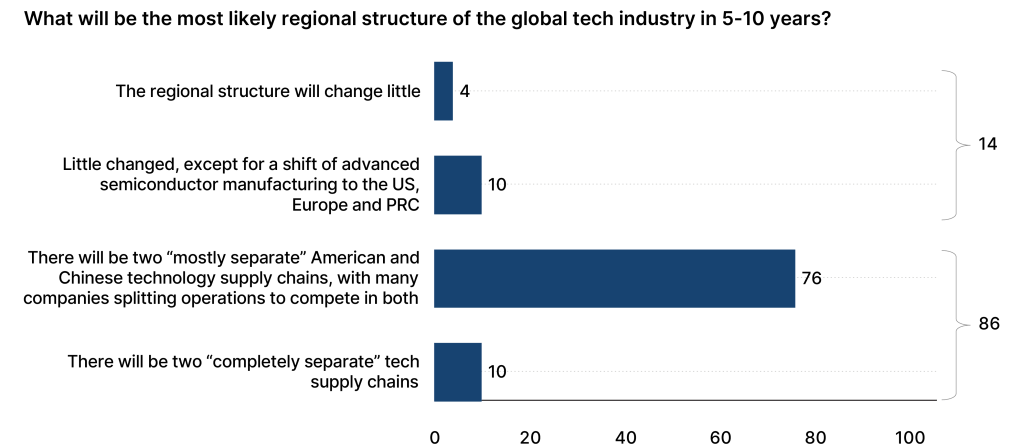

As the U.S. and China each adopt policies to accelerate technology competitiveness, it is vital to understand their potential global impact. The survey respondents overwhelmingly point to a future of greater bifurcation between the U.S. and Chinese markets, in which there are two competing ecosystems, but many firms operating in each.

More specifically, over 75% of respondents believe that two supply chains serving the U.S. and Chinese markets will emerge over the next five to ten years and that many companies will split their operations to serve both markets. Only 10% believe the U.S. and China will be served by completely separate supply chains.

Figure 11

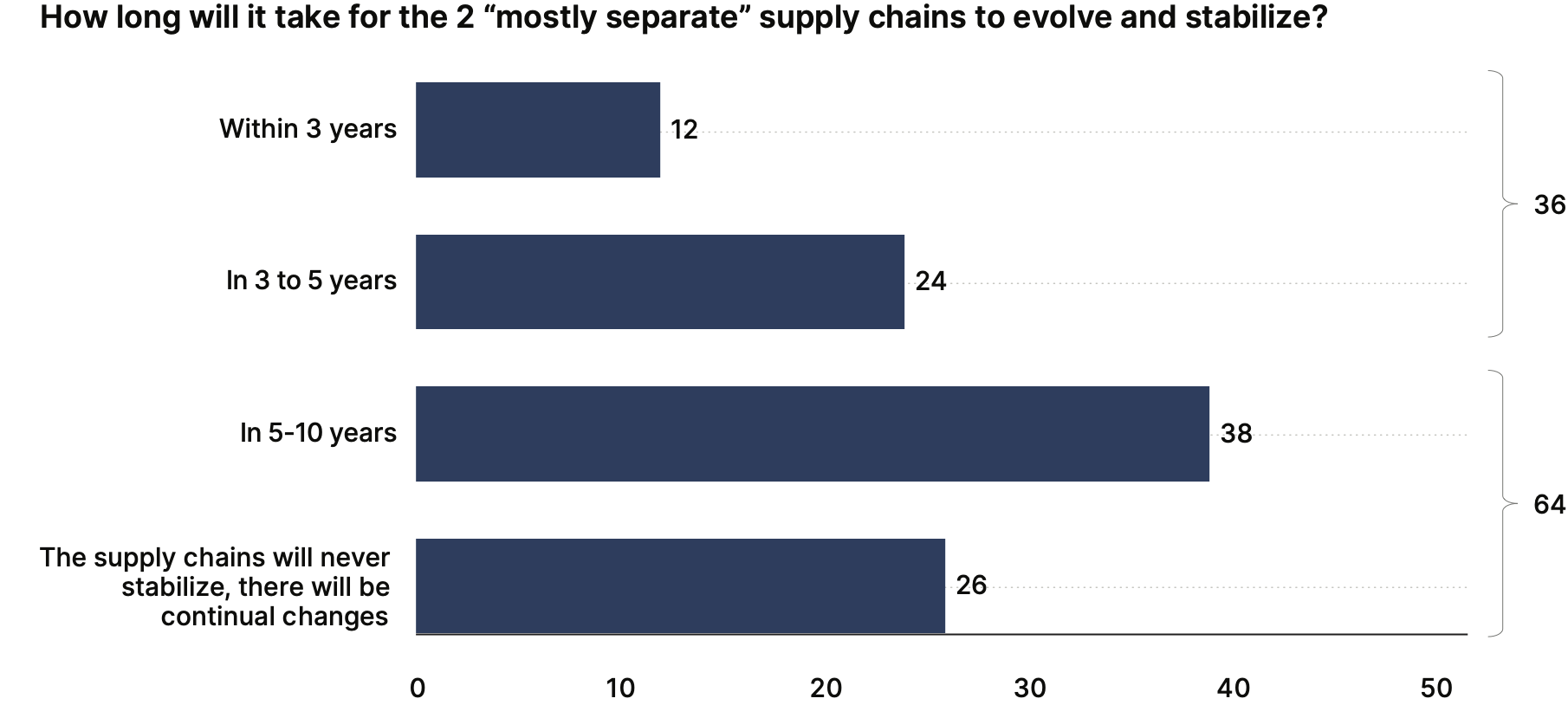

This separation will take time, with two-thirds of respondents indicating supply chain stability will take more than 5 years to achieve or “will never happen.”

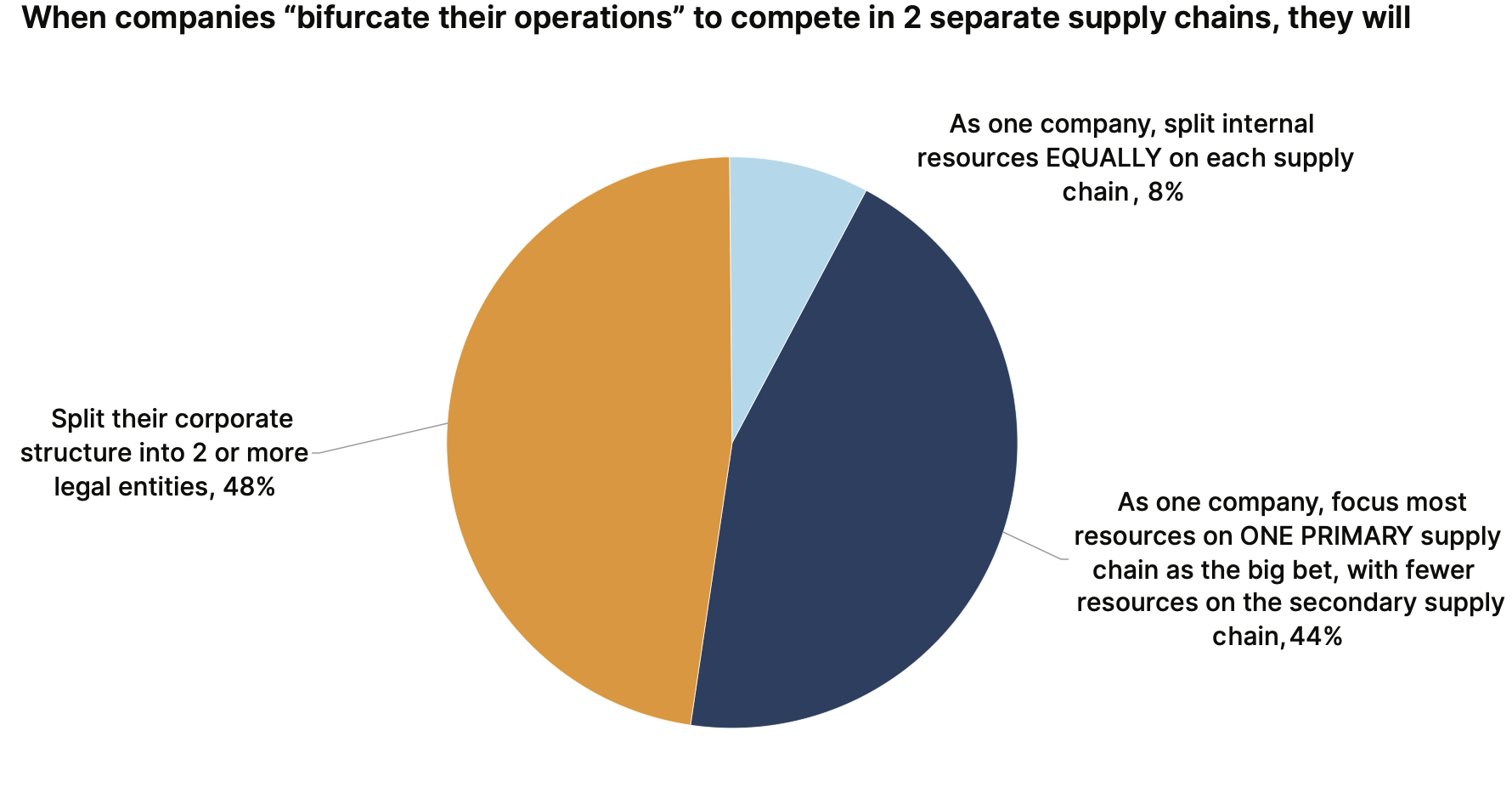

Figure 12

Respondents believe that companies will have to “choose sides”—not in terms of which “country to support” but in terms of which “supply chain to prioritize” with their investment and their talent. Nearly half of respondents believe that companies will prioritize just one of the 2 global supply chains; conversely, almost as many respondents anticipate that firms will split up their operations into two separate legal entities focused on the two separate markets, despite the challenges associated with dividing an existing set of engineering, know-how, and patents between 2 different companies.

Figure 13

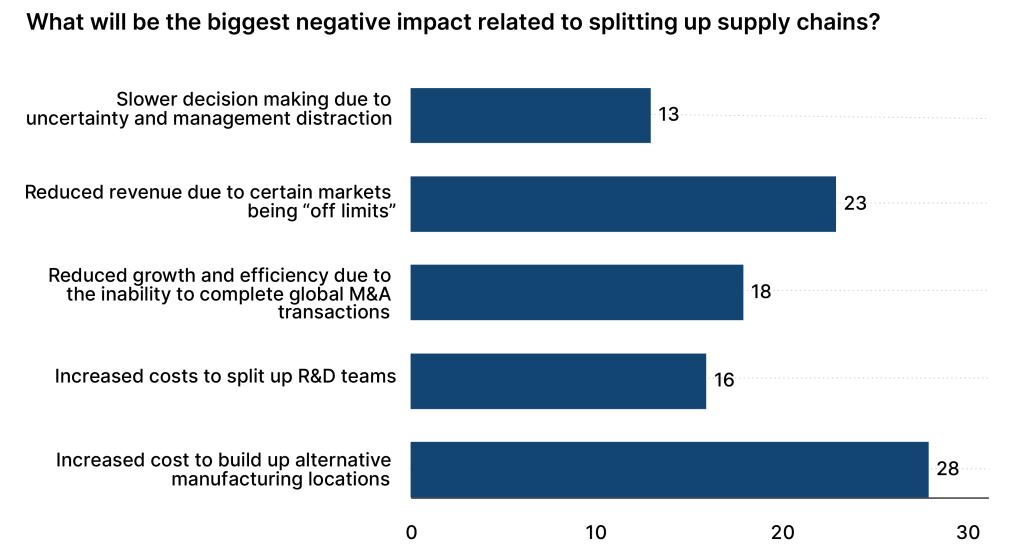

Respondents who work for operating companies, as opposed to financial services or research institutions, indicated this “splitting of supply chains” will have a negative impact on company operations, ranging from capital costs for building out redundant manufacturing sites to the “leadership costs” incurred as companies focus more on government policy than making great products and services.

Figure 14

The full range of negative impacts to company operations poses a challenge to government policymaking. Manufacturing subsidies are often viewed as an attractive policy lever for de-risking, for example, but they only solve one of the five major issues identified above; there is no “silver bullet” that governments can use to mitigate every impact of bifurcation.

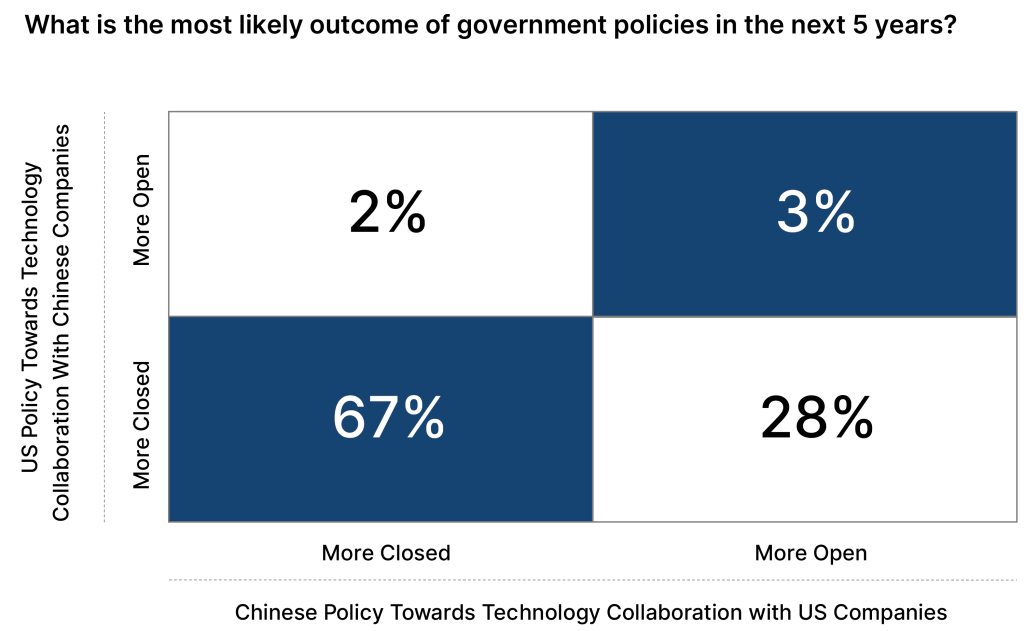

Respondents signaled that the driving force bifurcating the industry will be U.S. and Chinese policies. Only 5% of respondents’ express optimism that U.S. policies will become more open towards Chinese technology collaboration, while less than one-third believe Chinese policies will become more open towards U.S. companies. Strong belief in the continued and mutual closure of the two leading technology countries toward the other underlies respondents’ overall survey responses.

Figure 15

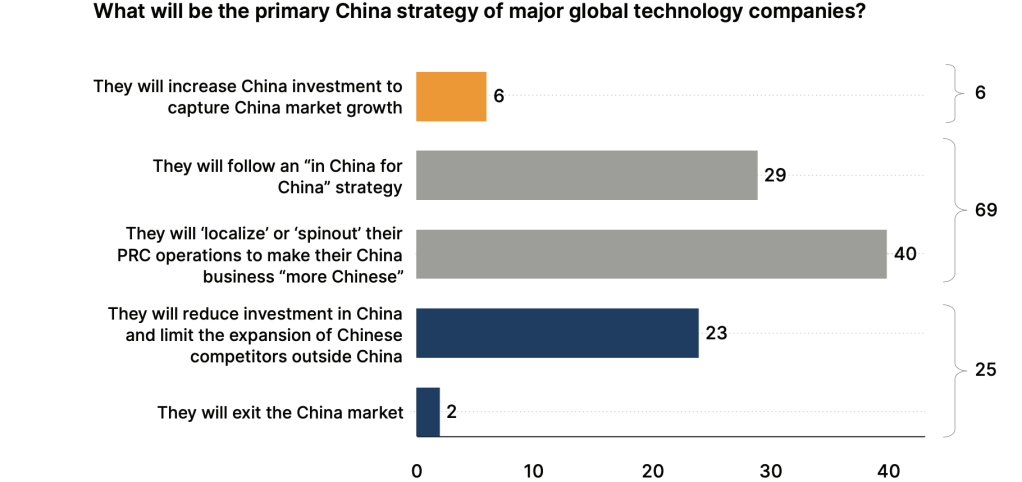

De-risking is complicated by the reality that U.S. policies will not stop global companies from serving Chinese markets. Respondents may have considerable optimism about the US, but 70% also believe that global companies will continue to do business in China, albeit in a different manner than they would in other markets. More than two-thirds of respondents indicate companies will split off their China business, either via offering unique products and services, or by spinning out their business to local investors.

Figure 16

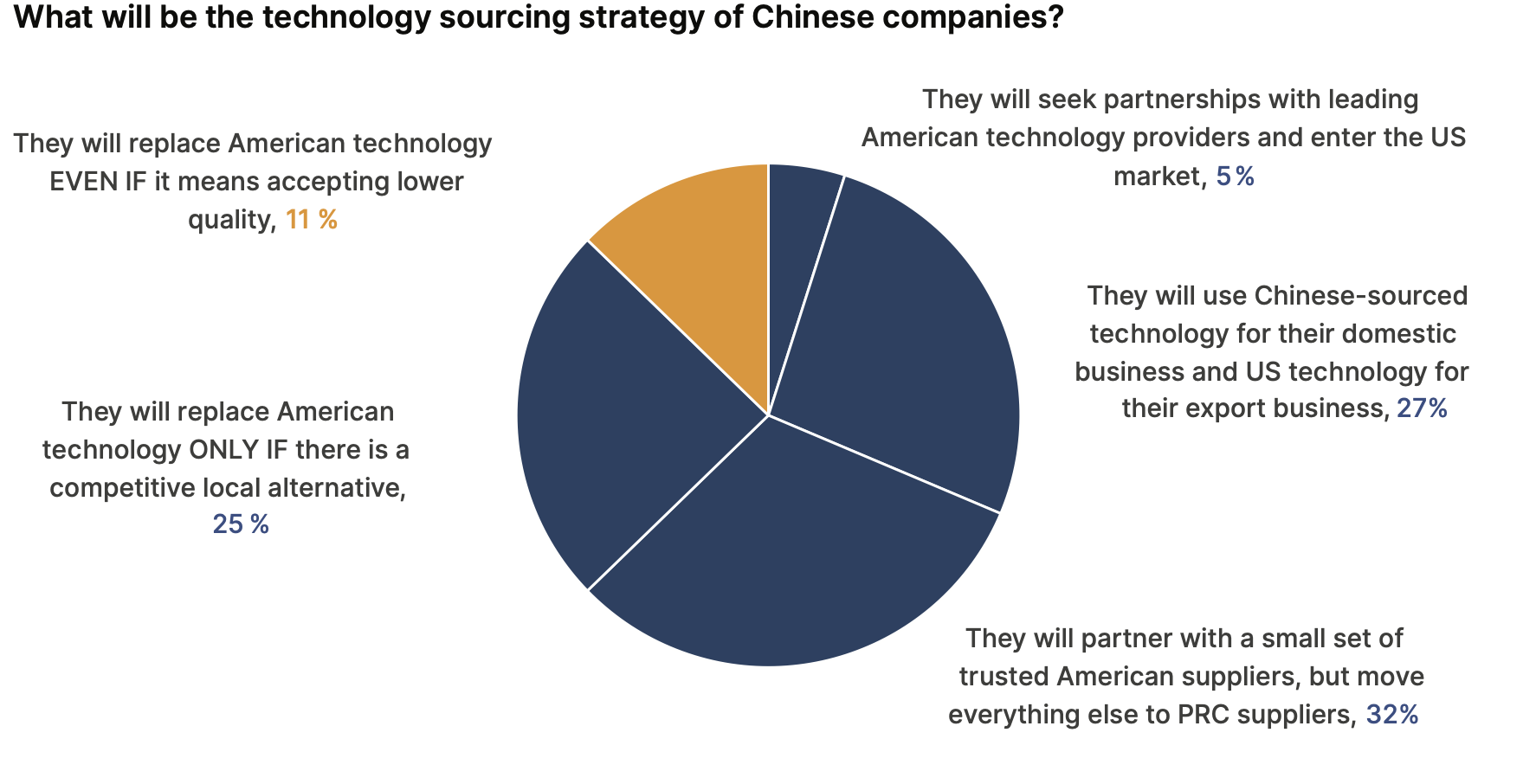

Respondents expect American firms to continue operating in China because, despite the considerable challenges of doing so, Chinese customers will still purchase products from and partner with American companies. In fact, less than 15% of respondents believe Chinese customers will fully shun American technologies and products.

Figure 17

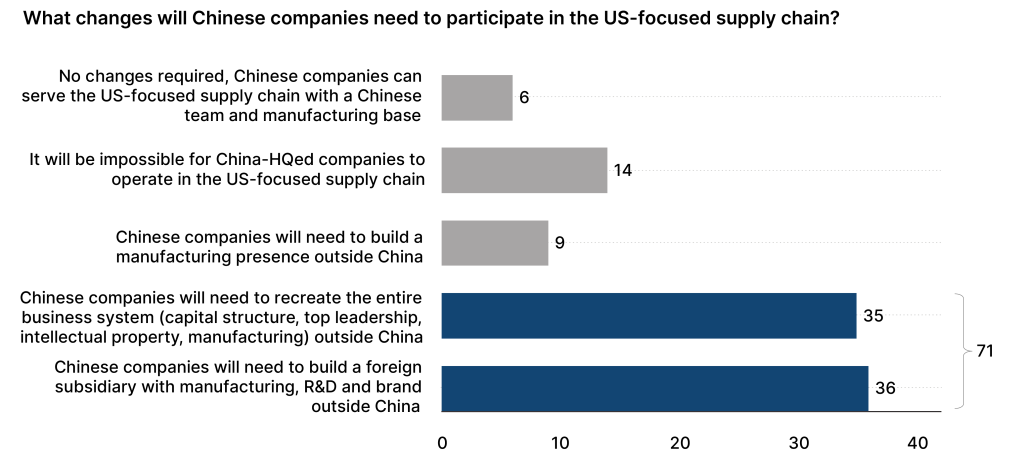

Finally, when it comes to bifurcation, it’s worth noting that “splitting up the business” is not solely a task facing non-Chinese companies that operate in China. Chinese companies too will need a similar approach when they want to work in the “US-led” alternative to the Chinese-centered supply chain: more than 70% of respondents indicate that Chinese companies will need to move substantial research, development and manufacturing operations outside China to compete in the US-led ecosystem.

Figure 18

Building on strengths: U.S. policies to maintain global technology leadership

The U.S. must be clear-eyed when evaluating its policy responses to competition from China. In light of the survey results above, American policymakers would do well to heed three points in particular.

First, the U.S. occupies a strong position. For a technology ecosystem to win in the long-term, it needs to consistently attract more capital and participants than any competing ecosystem. In this light, the survey results should be welcome news in the White House: the survey respondents indicated they expect more capital and more talent will flow into the U.S. ecosystem than any other. The U.S. ecosystem is already expected to win out.

Second, the Chinese strategy of ‘technology self-reliance’ is unlikely to succeed. Any policy framework that preferences local Chinese companies within the Chinese market is unlikely to be a game changer in attracting global capital and talent into China. And since Chinese companies acting alone cannot build a stronger ecosystem than one in which a broader range of U.S. and global companies compete, it is unclear how such a strategy will better position Chinese firms in global markets either. In addition, global businesses that restructure their China efforts to “localize” or “invest in China for China” are unlikely to use China as a global manufacturing or R&D location. A disinterested observer would advise the Chinese government to change its strategy towards becoming a far more competitive destination for global capital and talent. Ultimately, Beijing will need to reckon with the reality that no country can pursue both technology self-sufficiency and global integration at the same time.

Finally, given the strength of the American position and the challenges facing Beijing, the results suggest that the U.S. strategy for technology competition does not require a radical overhaul. Instead, U.S. policies should reflect a steady confidence in the strength of the U.S. innovation and technology system. Every Chinese company that builds U.S. hardware and software into a Chinese electrical vehicle, or integrates American chips into Chinese phones shipped to Africa or Vietnam, increases the size and the strength of that U.S. ecosystem. Policies should encourage American companies to pursue those opportunities. To be sure, the U.S. government can and must remain hardnosed about protecting U.S. intellectual property, limiting the spread of militarily-sensitive technologies, and improving market access, among other issues. But a major rethink of U.S. policy is not needed. The American technology ecosystem is already on track to be a big winner – provided it doubles down on attracting the world’s best talent and smartest capital.

Source link